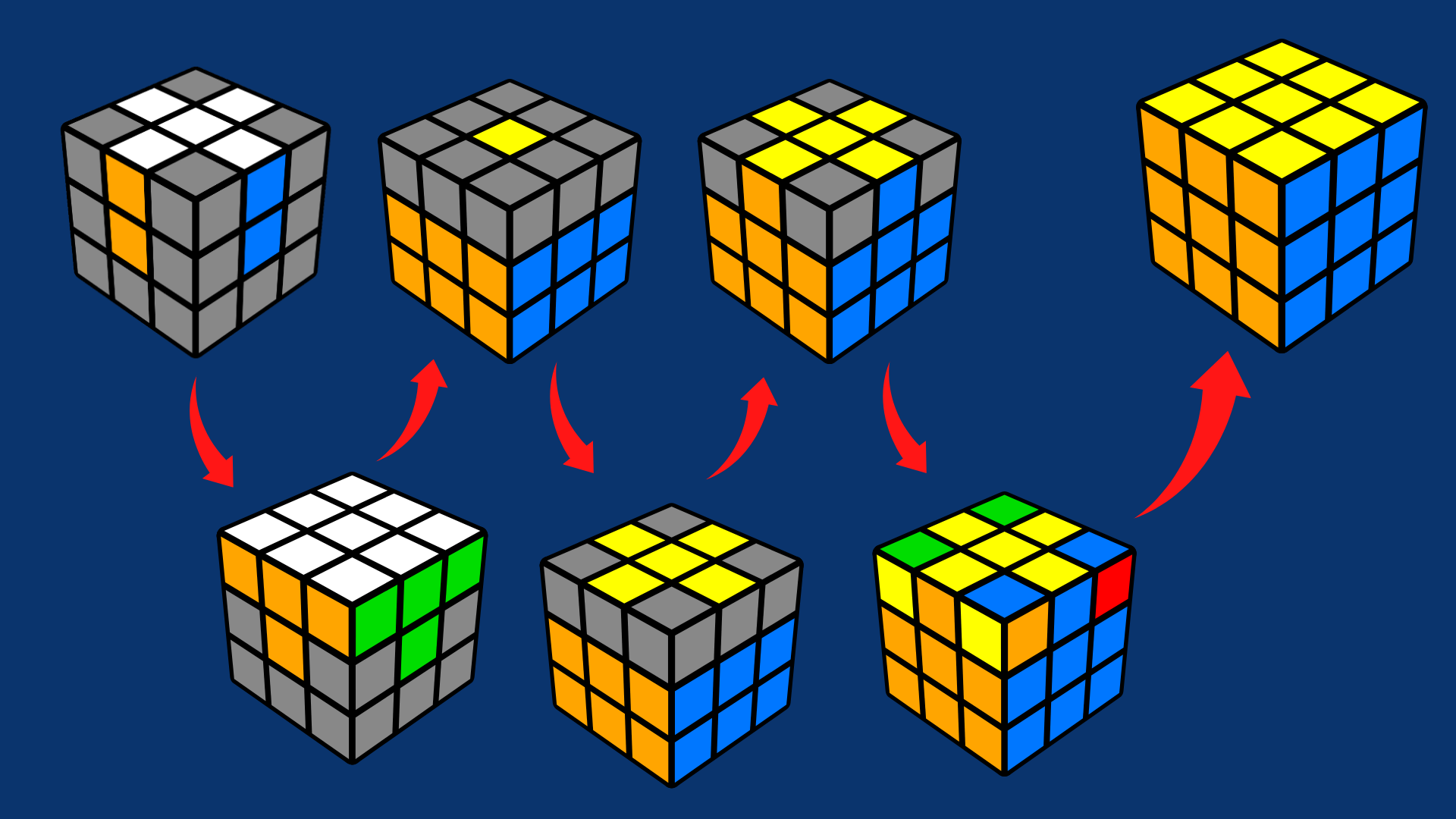

Using algorithms and look-ahead, the most fleet-fingered cubers in the world average between 50 and 60 moves per solve, which they can execute almost without thinking. This minimizes time-consuming pauses and can give observers the impression that a speedcuber is solving the cube in one uninterrupted string of maneuvers. A kind of short-throw clairvoyance, look-ahead enables cubers to plan for future algorithms a fraction of a second in advance. The very best speedcubers excel at something called “look-ahead”-the ability to spot the pattern that will snap into existence right as they finish the move they are currently performing. Stringing algorithms together is a skill unto itself. When a speedcuber spots an arrangement they recognize, they perform the corresponding algorithm, bringing the cube one step closer to solved. Knowing which to use when boils down to pattern recognition: Each algorithm corresponds to a different arrangement of colored squares on the cube.

Elite speedcubers will commit hundreds of algorithms to memory and practice performing them in their idle moments. This is perhaps the greatest misconception among people unversed in the ways of the cube: Anyone who solves the puzzle quickly does so not by sheer intuition, but with memorized sequences of moves, called algorithms, which they deploy to solve the cube section by section. “That's just not something humans can do.”Įven if humans could identify the most efficient solution before executing a single turn, actually performing that solution might not be faster than speedcubers' current methods, which depend on deeply ingrained muscle memory and hair-trigger reflexes. “There's nobody out there that can look at this cube and say, ah, I'm 18 moves from solved, and this one takes me to 17,’” Rokicki says. In the end, Rokicki’s team proved that every Rubik’s Cube scramble can be solved in 20 moves, and that the vast majority of them can be solved in even fewer.īut just because a computer can identify the most efficient solution to a scrambled cube doesn’t mean a human can. Their proof by exhaustion would have taken a normal computer decades to perform, but Google’s machines cut the compute time to a few weeks. But in 2010, Rokicki and a small team of computer scientists convinced Google to let them brute-force the problem by using the company’s computers to find the most efficient solution to all 43 billion billion starting configurations. Which is why, for many years, no one knew for certain how many moves were required to solve the cube's most Gordian scrambles.

“That’s more positions than there are grains of sand on all of Earth’s beaches.”įorty-three quintillion-43,252,003,274,489,856,000 to be exact-is the kind of number that defies analysis. “There are more than 43 quintillion ways to scramble a Rubik’s cube,” says computer scientist Tom Rokicki. “Since 2010, I’ve broken the Average-of-5 record probably 10 times,” he says. Zemdegs’ 5.69-second average was an 0.11-second improvement over his previous best, which was also a world record. When they're finished, competitors eliminate their fastest and slowest times and calculate the mean of the remaining three. (The toy you're probably picturing is just one of many mechanical riddles belonging to the genus of so-called twisty puzzles.) Last month, at a speedcubing competition in Brisbane, he set a new world record of 5.69 seconds in the Average of 5 event, wherein contestants each solve five cubes that have been scrambled according to computer-generated instructions. Zemdegs holds numerous cubing records, but he is best known as the most consistently swift solver of the 3 by 3: the canonical three-layered, Mondrian-colored cube. No matter: It takes him less than seven seconds to transfigure the cube in his hands from scrambled to solved. He looks like he hasn’t been awake for more than 20 minutes. On it: a big, squishy, Rubik’s Cube novelty pillow.

Over his shoulder, I can see his unmade bed. It’s early in Sydney, where he’s speaking to me over video chat from his apartment. “It’s my first solve of the day,” says Australian speedcuber Feliks Zemdegs, somewhat sheepishly. Even on my laptop’s tinny speakers, the sound is unmistakable: the click-clacking, slip-sliding sound of a Rubik’s Cube whipping into shape.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)